Scott Dochterman

April 11, 2022

SOLON, Iowa — If NFL executives wanted to

watch Iowa center Tyler Linderbaum squirm during formal meetings at

the scouting combine, they wouldn’t critique his worst plays. They’d praise him

for his best snaps.

“You can never say anything good about the guy. Ever,” said Iowa

quarterback Spencer Petras, one Linderbaum’s roommates and closest friends.

“He’ll just tell you to be quiet or like, ‘Eff off.’”

Rarely do anything but

superlatives enter conversations about Linderbaum, the undisputed top center

candidate in this year’s NFL Draft. He was a unanimous first-team All-American,

the Rimington Trophy winner and an Outland Trophy finalist.

Sure, there are a few questions about his size (6-foot-2, 296 pounds) and it

wouldn’t be draft season if arm length (Linderbaum’s measured 31 7/8 inches)

didn’t enter a discussion. But his on-field play became the gold standard for Pro Football Focus,

which ranked Linderbaum as the nation’s top center two consecutive years.

Linderbaum’s personal

qualities are as apparent as his on-field prowess. When collegiate athletes

were granted rights to monetize their name, image and likeness, Linderbaum sold

personalized sweatshirts and donated every cent to the UI Children’s Hospital.

He graduated with a degree in enterprise leadership in only seven full semesters

at Iowa. He played his final quarter as a Hawkeye with a mid-foot

sprain that kept him from on-field workouts at both the NFL combine and Iowa’s

pro day.

Of all the traits that

draw people to the 22-year-old Linderbaum, it’s his loyalty that wins them over. As

a high school senior, Linderbaum wanted one final experience with his friends

at Solon (Iowa) High School and played school-sponsored baseball with a season

that stretched into mid-July. Those afternoon practices and night games

coincided every day with his 6 a.m. workouts in the Iowa football weight room

and 11 a.m. summer classes. Despite his lack of consistent sleep, Linderbaum

missed only one baseball practice, no football workouts, and his baseball team

qualified for the state tournament.

“It gave him that opportunity where he knew, ‘OK, this is what

I’m accepting,” said Todd Linderbaum, Tyler’s father. “‘It’s allowing me to

have one last fling with my high school buddies in baseball, but also to

transition into something that it’s going to lead me into the future.’ I think

he kind of had the best of both worlds.”

Linderbaum didn’t complain about his 18-hour days. He liked the

daily structure and he had help from his family, including a grandmother who

brought him food. His mother, Lisa Linderbaum, called it “a team effort.” It

was a challenge but one he fully accepted.

‘He didn’t like to lose’

Growing up in Solon, where his family home is exactly 15 miles

north of Kinnick Stadium, Linderbaum became competitive with his older brother,

Logan, from the moment he could walk. Logan was 3 ½ years older, and they had

their frequent skirmishes. The age difference was amplified in early

competitions, but Linderbaum wouldn’t quit battling, whether it be in sports,

Ping-Pong or a family board game.

“He didn’t like to lose,” Lisa Linderbaum said. “That’s what I

always tell Todd. We should have made him lose as a little boy more often than

he did. Just because if he didn’t win, he was pissy.”

Linderbaum had to prove himself and wasn’t given anything by his

brother. He had to earn his at-bats or snaps in neighborhood games. When

Linderbaum was in third grade and playing flag football, his father coached

Logan’s sixth-grade tackle football team. Logan’s team was short on players one

day, so Linderbaum was told to stand in as a cornerback but not compete in any

drills.

“Before I knew it, he kept creeping up and creeping up and he’s

almost at middle linebacker right over our tackles and guards,” Todd Linderbaum

said. “Oh, buddy, with no pads on, of course. He wanted to get in there and

play. He wasn’t about to sit out there and just be a statue and just be an

extra number for dad and other coaches.”

As he grew, Linderbaum played every sport, but basketball was

his favorite. Logan was a state-qualifying wrestler and eventually earned a

scholarship to compete for Minnesota State-Mankato. Although Linderbaum’s size,

strength and frame screamed wrestler like his older brother, he wouldn’t give

up basketball until his sophomore year. When Linderbaum finally traded in shorts

for a singlet, he had to learn the sport’s technical aspects, which proved far

more difficult than using natural athletic ability.

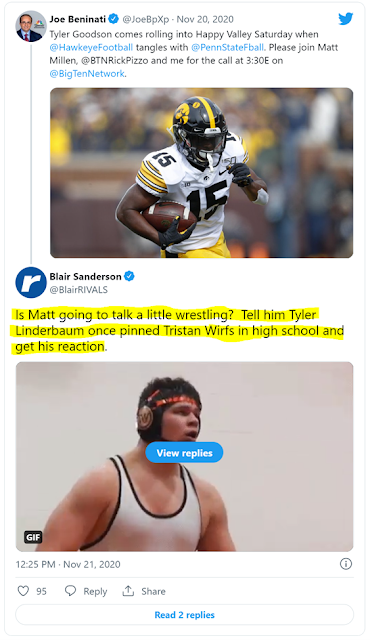

Linderbaum’s transition

to wrestling added to one of the great high school competitions in eastern Iowa.

Solon’s archrival is Mount Vernon, which is located eight miles to the north.

At tournaments and duals throughout the region, Linderbaum regularly saw and

battled Mount Vernon’s Tristan Wirfs. Although they were friendly, their

temperaments were completely different. Wirfs was an easygoing giant with

freakish size and strength. Linderbaum was smaller but made up for it with

intensity and tenacity.

“It got harder every time,” Wirfs said. “I knew it was always

going to be close. But I was always nervous because he’s like a bulldog. He’d

come out all fighting and stuff. I’m like, ‘All right. I’ve got to slow things

down. This is too fast.’”

Wirfs beat Linderbaum every time by fall through three regular

seasons. Then, the schools were matched up in a regional dual with the winner

qualifying for the team state tournament. Solon already had locked up the dual

meet by the time Wirfs and

Linderbaum met in the heavyweight match. Wirfs tried to throw Linderbaum as he

did in every previous matchup. This time, Linderbaum caught Wirfs, powered him

to his back and pinned him with six seconds left.

https://twitter.com/BlairRIVALS/status/1330200772320108544?s=20&t=73wzpnKk0B5FHeCRP5xSgA

“The

night of those matches, there was some juice to it, let’s not kid yourself,”

Todd Linderbaum said. “Two combatants going at it, and two pretty competitive

kids, obviously. Tristan got him every time but one. That was quite the night

out there.

“I would say a friendly competitive rivalry of two young kids

just giving it their all is what those were, but good intensity to say the

least.”

Wirfs won the Class 2A individual heavyweight title a week later

while Linderbaum helped

Solon claim the Class 2A state team title. They later became teammates

and friends at Iowa and started on the same offensive line during the 2019

season.

“He got me on the last one at the end of the dual,” Wirfs said.

“That’s the one everybody remembers.”

Without fail, Linderbaum mentions that Wirfs won the other

matchups.

“We’ve always competed against each other, whether it be

football, baseball, track, obviously wrestling,” Linderbaum said. “I’ve

wrestled him quite a bit. He’s beaten me quite a few times. I’m happy I got one

match on him, but he’s a great competitor. He’s someone who’s made me better.”

‘The best I’ve

seen’

Linderbaum signed at Iowa as a defensive tackle and played in

two games while redshirting in 2018. During postseason bowl preparation, Iowa

coach Kirk Ferentz asked Linderbaum if he would consider moving to center. In a

move that still fires up the program’s defensive coaches, Linderbaum agreed.

By the next spring, Linderbaum was firmly entrenched as the

first freshman to start at center in 13 years. He and Petras carried footballs

around campus and Linderbaum would snap to his quarterback.

“That’s a good example of trusting your coaches and being

coachable,” Lisa Linderbaum said. “You allow yourself to do that.”

Despite his lack of experience, Linderbaum became the tone-setter on an offensive line

that included Wirfs and four-year starting left tackle Alaric Jackson, both of

whom were first-team All-Big Ten honorees. Linderbaum battled daily

against defensive tackle Daviyon Nixon, who was a first-team All-American

in 2020, and the young center forced his defensive teammates to match his tempo

in practice or suffer the consequences.

“Some days felt longer than others,” Iowa defensive tackle Noah

Shannon said. “Every day I came to practice it felt like game day for me when I

went against Lindy. He is just a great competitor, and he’s not dirty or

anything like that; he’s just trying. It’s all effort with him, and I knew I

was going to have to give 100 percent because he’s not coming with anything

less.”

“The biggest thing is

he’s always in good position with his hands and his leverage,” Iowa defensive

tackle Logan Lee said. “He’s just a freak of nature. He’s just able to cover so

much ground and he’s able to make something out of nothing, especially like

at the start of the rep if you happen to be winning, he’ll typically find a way

to finish the rep on top.”

According to Pro Football

Focus, Linderbaum allowed only two sacks in 1,201 pass-blocking snaps over

three seasons (0.17%). Linderbaum was ranked as the nation’s fifth-best center

as a redshirt freshman in 2019 and No. 1 in 2020 and 2021. Last year, he graded

as the best center since PFF began evaluating college players nearly 10 seasons

ago.

Iowa’s staff asked him to do more than most centers in its

outside zone with reach blocks on three-technique defensive tackles. Linderbaum’s quickness and

ability to reach second-level defenders off a combination block are rare.

His hands, leverage, speed and tenacity helped him win snaps against larger and

stronger defensive linemen.

(Tony Quinn / Icon Sportswire via Getty Images)

Kirk

Ferentz regularly downplays player comparisons, and with good reason. He was

the offensive line coach when the Baltimore Ravens drafted Jonathan

Ogden in 1996. At Iowa, Ferentz coached Robert Gallery (2003) and Brandon

Scherff (2014) to Outland Trophy seasons and honed Eric Steinbach (2002)

and Wirfs (2019) into first-team All-Americans. Another former Iowa pupil,

Marshal Yanda (2005-06), was a unanimous member of the NFL Team of the Decade

for the 2010s. So when the old line coach evokes a historic name, even in

passing, he does so for a reason.

“The thing that jumps out

most to me about him is his consistency,” Ferentz said. “I

go back to growing up as a young person. Mike Webster was a guy, boy, was he a

good center. I remember going up to Latrobe (Pa.) and watching them practice.

He made everything look easy. You know it’s not easy, blocking a guy like Joe

Greene. After practice, Joe Greene and he went one-on-one. What do you think a

ticket like that would cost if it was for public consumption? Two of the

all-time great NFL players.

“Just the things he did, the work, the consistency. Just looked

like it was almost easy. It’s not. There’s nothing like that, especially in the

NFL or what we’re doing. That’s

how I would describe Tyler. So efficient, so focused and usually pretty sound

fundamentally. He wins a lot of battles because of that.

“The other part I would just say about him, you meet him, I

don’t know if low key is the right word, but he’s not an outward rambunctious

guy. He’s

ultra-competitive.”

Teammates, college rivals and evaluators alike appreciate what

Linderbaum brings to every competition.

“He’s definitely just like

you guys see,” said Wisconsin first-team All-American linebacker Leo Chenal.

“He’s really fast, he’s super athletic, he’s definitely earned the top whatever

lineman, definitely at his position. Because he’s fast, he’ll get to the second

level really quick, so you got to be careful.”

“We’ve had very good luck

with Iowa players over the years,” Ravens general manager Eric DeCosta said.

“Marshal Yanda, to me, Hall of Famer someday. When we look at a guy like Tyler

Linderbaum, we see a lot of the same qualities — tough, gritty, very, very

athletic, very intelligent, smart, the type of guy who could really be the

centerpiece of your offensive line. Teams picking in the top 15, I think have a

chance to get themselves a really good offensive lineman.”

Fellow Iowa offensive lineman Kyler Schott wrestled Linderbaum

in high school and played beside him the last few years.

“I’ve played with some

pretty good O-linemen: Tristan Wirfs, Alaric Jackson, Sean Welsh, Ike

Boettger,” Schott said, “and he’s the best I’ve seen out of all of them.”

Iowa’s most recent three multi-year starters at center

— James Ferentz (Patriots), Austin

Blythe (Seahawks), James Daniels (Steelers) — all are on NFL

rosters. Every starting Iowa center but one in the last 20 years, including

offensive coordinator Brian Ferentz, has signed an NFL contract. Brian Ferentz,

like Linderbaum, was a team captain his final season but he laughed at any

comparison between himself and his young protégé.

“I’m so flattered right now. I’m serious,” Brian Ferentz said.

“That’s insanity. That’d be the last time I’ve ever mentioned in the same

breath as Tyler Linderbaum as a player. Let me just relish it for a second. But what separates him? You

look, his physical ability. That’s probably No. 1 that separates him.”

Brian Ferentz then

described Linderbaum’s mentality and mindset also as separators.

“He’s like a unicorn,

and you’ll be chasing those forever,” he said. “I feel confident that I know

football and I know offensive line play. The hard part for me is the absurdity

of what you just said. It’s an insane comparison. He’s so good. I mean that

like he is so good. He is

on a different level than most players. Guys that I have a tremendous

amount of respect for as players. Austin Blythe, I think is a great football

player, and I love him. But if

we’re playing pickup football and I’ve got one pick, I’m taking Linderbaum.

Now, Blythe’s going to be mad at me, but that’s just the truth.”

Loyalty above all

For the power and swagger he displays on the football field,

Linderbaum shows affection easily off it. During his college career, Linderbaum

traveled to different Eastern Iowa communities to give football instruction or

walked into Solon’s wrestling room to help with workouts. He routinely met with

patients at the UI Children’s Hospital. None of those volunteer functions came

with a tweet of publicity.

“He wants to give back and he has the opportunity to give back,

but he also doesn’t want any (publicity),” Todd Linderbaum said.

“I was teasing Tyler’s dad,” Kirk Ferentz said, “I said he

probably rescued somebody out of like a burning house or something like that on

the way over to the children’s hospital. That’s the kind of guy he is.”

The one moment that drew attention to Linderbaum came with the

NIL repeal. For nearly two

weeks last fall, “Baum Squad” sweatshirts became hot products online, and they

raised $30,000. For a college athlete, it was a considerable amount of

money. Many of his teammates kept their NIL income or pledged a portion of it

to charity. Linderbaum

donated all of it to the UI Children’s Hospital.

“My whole mindset of it, whether it be $1,000 or $20,000 or

$30,000, I said I was going to give 100 percent of the profit,” Linderbaum

said. “I’m not too worried about how much money I have right now. With all the

NIL stuff, it’s kind of cool I can do stuff like this. I think having 100 bucks

is a lot, so I’ll be fine. I don’t have to pay for school with my scholarship,

so I’m living life fine. I think donating $30,000 to the children’s hospital is

more important than that.”

The

donation did not surprise his parents. Of course, his mother noticed his

appearance at the check presentation.

“Clearly he showed up in a torn jacket,” she said with a laugh.

“He’s just very grateful for the littlest things. Even as a child, he never

asked for anything, ever. He’s fine with his brother’s hand-me-downs. Always

has been. For us it’s like, ‘You need a new pair of shoes.’ ‘No, these are

fine. I have these.’ I’m like, ‘You need a new pair of shoes. There are holes

in (them).’ I mean, he makes do with what he has.”

While simplicity wraps his exterior, loyalty never strays too

far from Linderbaum’s makeup. He grew up an Iowa fan and when the scholarship

offer came his way, he jumped on it and never looked back.

Linderbaum had no interest in even entertaining the question

about whether he’d play in the Citrus Bowl against Kentucky. Late in the fourth

quarter when he suffered a foot sprain so painful that he couldn’t walk without

a serious hobble, Linderbaum returned to the field after missing just three

plays.

Although the injury kept him out of workouts for NFL scouts,

Linderbaum remained steadfast he made the right decision.

“I wouldn’t change it,” he said. “I’d play in that game if I

could again. Hopefully go out on a win.”

Linderbaum stayed in Iowa City to train this winter because,

“I’m not going to leave the place that helped me get where I’m at.”

With a bachelor’s degree

in hand and first-team All-American honors, Linderbaum had nothing

left to prove when he returned home from the Hawkeyes’ bowl game. Yet it took

him nearly two weeks to finalize his decision to leave for the NFL. He

announced his plan only three days before the deadline.

“He was still torn,” Todd Linderbaum said. “I think it’s maybe

twofold. One, you go back to the summer of his senior year with baseball. He

didn’t want to leave his buddies behind. I’ve gotta finish this out

here. I think the same analogy, maybe it could be used with football.

He didn’t want to leave his buddies behind.”

“It’s hard for him to make decisions, what’s best for me versus

what’s best for the team,” Lisa Linderbaum said. “This decision ultimately was

what was best for him, unfortunately, and fortunately.”

With few exceptions, the Linderbaum family met at an Iowa

City-area Hy-Vee and enjoyed breakfast together every Sunday morning. Often,

the family would ask him to do his laundry just to see him for a few extra

minutes or take him out to dinner. That all changes on draft night when NFL

commissioner Roger Goodell unveils Linderbaum’s football destination. Whether

it’s loyalty or love or just preference to avoid the spotlight, Linderbaum will

watch the draft with family in Solon.

“You take just those little tiny moments that you do get with

him and you enjoy it,” said Todd Linderbaum, who started to become emotional.

“Whatever happens, we’re just tickled that there’s an interest in our son to

play at the highest level of football. Wherever that direction takes him, oh

man, we’ll be there on Sunday watching him and supporting him.”

(Top photo: Robin Alam / Icon Sportswire via Getty Images)

.png)